-Abraham Lincoln |

|

'Sleepytime Down South' Author Leon Rene Revisits SU Campus

By Cleo Joffrion

Advocate Staff Writer

Standing on the bluffs above the Mississippi River in Scotlandville in 1915, a 13-year-old boy watched boats rounding the great bend of the river at sunset.

Standing on the bluffs above the Mississippi River in Scotlandville in 1915, a 13-year-old boy watched boats rounding the great bend of the river at sunset.

That image remained with him, and 17 years later in Los Angeles, Leon Rene wrote “Sleepytime Down South,” a song loved by millions worldwide and identified with the act of Louis “Satchmo” Armstrong.

Leon Rene returned to Southern University recently, the first time since his brief stint at the school 64 years ago to be recognized by the Southern University Band for his achievements in the recording and publishing industry and to present some memorabilia to the university library archives.

A native of Covington, the 77-year-old was last in Louisiana for the July 4, 1976 unveiling of a bronze statue of Satchmo in New Orleans. Before that, he hadn't visited the state in 40 years.

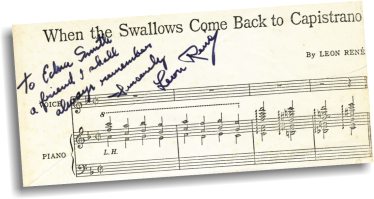

“Sleepytime” has been inducted into the Hall of Fame of the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers. Other memorable songs written by Rene included “When the Swallows Come Back to Capistrano” and (for those whose memory doesn't go back that far) the original version of “Rockin' Robin,” a hit for the Jackson Five in the 70s and more recently recorded by Rene's son, Raphael.

Although Rene's father, a contractor, played violin and his mother, the piano, Rene had very little formal musical training. He said he learned to play the piano from his cousin. The first song he learned was "Brown Skin, Who You For? You Sho Look Good to Me.”

Rene said he was often asked to play at parties. “I'd play that song all night. I just had different versions of it.”

He got his start as a pianist in Covington at the “colored” picture show during summers, then moved to the “white” show at the age of 15 for a $1 a week raise. By then, he said, he had added other music to his repertoire, such as musical phrases for thundering hoofbeats and for trouble looming ahead.

“I got the job because the former piano player played boogie woogie during the love scenes,” which didn't sit too well with the patrons of the manager, he said. When movies began to have written background music, however, Rene said he was fired because he couldn't read the score.

While living in Covington, he also served as a fill-in for the band of New Orleans coronetist Buddy Petit in a performance at the old Southern Hotel.

Rene said his education at Southern was short-lived when the school's head caught him and another fellow cooking some sweet potatoes, on an open fire, that they had “encouraged to come out” of a field on campus. Since he was 13 years old and the school's admittance age was supposed to be 14, Rene said his age was used as an excuse, and he was asked to leave.

He said he never forgot, however, the time he spent on the banks of the Mississippi, and that served as his inspiration years later for “Sleepytime.”

Rene's family moved to California after World War I, and they bought a house in Pasadena.

Having dropped out of school before graduation, Rene said, “I didn't know what I wanted to be. My father wanted me to be a bricklayer, and my mother hoped I'd be a lawyer.” So he ended up laying bricks during the day, working with his father, and playing the piano at night.

While working as a bricklayer, Rene said he would “wear gloves because I didn't want my hands to get dirty. And besides, laying bricks made my hands so hard, I couldn't make the runs on the piano.”

Rene said he and his brother Otis, a pharmacist, first collaborated on a song for a contest sponsored by California Maid products called “My California Maid.” They won first place out of 6,000 contestants, but he discounted it as the beginning of his songwriting career, since “it wasn't commercial.”

The recording of “Sleepytime” by Armstrong was his 'first big moneymaker,” he said.

Again, he and Otis collaborated, with Otis providing the melody. The song was written for a play “Under Virginia Moon,” which folded in three weeks, and was taken from a line of a character in the play.

Rene met Satchmo when Armstrong opened at the Cotton Club in Culver City. He told Armstrong about the song and invited him to his mother's house for a gumbo supper.

Satchmo came, loved the meal and the song and vowed he would record the latter, which he did. It became his standard opening number.

Rene had a couple of stories to tell concerning the creation of “Capistrano” in 1939, a song concerning a town 60 miles from L.A. from which the swallows leave every October to go south and return every March.

At the time, he was recovering from tuberculosis, and money was tight. One morning, he awoke, and his wife seemed reluctant to prepare his breakfast. He said he told her “Maybe when the swallows come back to Capistrano, I'll get my breakfast.”

Immediately, he thought that line would make a good title for a song and sat down to compose the first part of it. After his wife came in to compliment him on the sound and to bring him a hearty breakfast, he took that as a good omen and finished composing the number.

All that was left was to find a publisher for his creation. Rene said the biggest New York publisher at the time, Shapiro Bernstein, turned down the song because he said no one would know where Capistrano was. Rene said Bernstein tried to convince him to change it to “ When the Swallows Come Back to Alabama,” since everyone knew the location of Alabama. But Rene refused.

Finally, on the 18th day of prayer by his wife, a Catholic, for his health and the sale of the song, Rene said a contract and a $500 advance came from a Warner Bros. publishing firm in New York for “Capistrano.”

Two months later he said the song was being recorded by some of the biggest bands in the nation.

Rene also got into the recording end of the business early on because he said it's important to have control of one's music.

One of the first musicians he was responsible for recording was Joe Liggins, who wrote the song “The Honeydrippers.”

Rhythm and blues songs were banned from the radio at this time, “so you were blocked from the standpoint of exposure,” said Rene.

He said he had a demo record made of Liggins' tune, which he persuaded a jukebox distributor to place on one machine.

“It was a smash hit,” he said, and keeping up with the orders that resulted was a problem. Rene said he had guys with record presses in their backyards making the records.

“It didn't take much to get in (the recording business) in those days,” he said. Now, he said, recording one song can cost $25,000.

Rene also said he discovered Nat King Cole when Cole was a pianist with a trio on Eighth Street in L.A. Cole recorded four records with Rene, went to Decca Records, then recorded another song for Otis before going with Capitol Records.

Rene said the irony is that a partner in the record business nixed the idea of Cole's recording “Sweet Lorraine,” which later became a big hit, on the grounds that it was a ballad.

Rene is a bit contemptuous of popular songs on the market today.

"Some songs today don't have anything to say,” he said. “A band develops a particular sound, and they use that sound in all of their records. So it's the sound that's selling, not the song.”

He conceded, however, that many groups make huge amounts using this technique “so it's not to be sniffed at.”

But he remarked wistfully that those types of songs won't be remembered as time goes by.

Rene, who is presently head of Leon Rene Publications, ASCAP, in Los Angeles, was invited to Southern after Westdale Middle School librarian Edna J. Smith read of his visit to New Orleans two years ago. She called Rene earlier this year, then contacted Southern band director Isaac Greggs, and the visit was arranged.

Rene was greeted at the airport by Southern's band and Greggs was guest of honor at the bank banquet. The next day, he gave a talk to band students interspersed with some of his hits.

“You'll never know how if feels to be honored like this,” the slim, amazingly agile septuagenarian remarked. “Usually, songwriters make money, but they end up in the background.”

Contact Us | Homepage