-Abraham Lincoln |

|

Big Chief says tradition drives Mardi Gras Indians

6A Saturday, Baton Rouge;

Louisiana Saturday February 24, 2001 *

By Amy Wold

Advocate Staff Writer

|

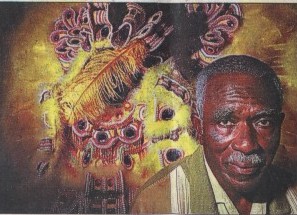

| Allison 'Tootie' Montana is a longtime Big Chief of the Yellow Pocahontas tribe in New Orleans. Each year, he meticulously creates a costume with hand-strung beads and ornaments for the Mardi Gras Indian festivities on Fat Tuesday. He will give a presentation today at the Bluebonnet Regional Library about his more than 50 years as a masking Indian. |

Since 1947, Big Chief Allison "Tootie" Montana, 78, of the Yellow Pocahontas tribe in New Orleans, has continued a family tradition he traces back at least 140 years.

Through designing and constructing a new suit almost every year of the 50 he spent masking, Montana has helped to keep the history of Mardi Gras Indians alive. He will display some of his beaded costumes, demonstrate songs and dances and discuss that history at a free event at 2 p.m. today at the Bluebonnet Regional Library.

Edna Jordan Smith, who teaches ancestral research skills at the library, organized Montana's presentation.

"I have found that Baton Rouge and New Orleans are really two different areas when it comes to knowing culture," Smith said. So, Smith said, she wanted to help educate people about this portion of African-American history. "I've met young people and older people who never heard of the New Orleans Mardi Gras Indians."

Mardi Gras Indians started in the 1800s as the African-American community's answer to the Mardi Gras parades and as a way to show respect to the Native Americans who sheltered, helped and supported African Americans during slavery, Smith said.

On Mardi Gras morning, the "tribe's" Big Chiefs, Spy Boys and Wild Men start their march into other "tribe's" neighborhoods looking for a confrontation. The Spy Boys serve as the lookouts and march three blocks from the Big Chief. When they spot another tribe, the Spy Boy signals to the Flag Boy, who in turn signals the Big Chief that they're about to meet another tribe. The Wild Man keeps the crowd open so the Big Chief can pass.

"Your biggest point was to catch another chief in his neighborhood," Montana said. If you knew you were "prettier," you could show up the other chief while he was surrounded by his neighbors. There's no official judging, but the people know who wins, he said.

"He'll know you're prettier than him," Montana said. "The city knows who the man is." Being the "prettiest" is now the mark of who wins the tribal battles, but that wasn't always the case. "Long time ago, you didn't have to be pretty, it was about fighting," Montana said. "It's a serious game they used to play out there." The Mardi Gras Indian day was a time to repay old grudges and decorated guns and knives were part of the costume.

"People used to enjoy Carnival through the shutters," Montana said.

When Montana first started masking at age 24, his mother would pin a Catholic medal over his heart and pray for him until he got home.

"I stopped the fighting," Montana said. "Rather than fighting, we fight with the suit. 'Get prettier than me.'"

Montana started masking in 1947, a year after returning from work in the shipyards of California during World War II.

That year, his father was asked to help start a new tribe in the 8th Ward, and Montana decided to get involved too and masked for his first time.

"A little two-week-old suit," Montana said. Since that first time, Montana has started his suits the night after Mardi Gras and works on them all year.

Although Montana hasn't masked in the last couple of years, he hasn't given it up yet. "I intend to come back next year because the people don't seem to want me to quit," Montana said. However, he said, he's going to change the way he makes the suit to make them lighter than the usual 100 to 200 pounds.

"It's going to be just as pretty, but it won't be as heavy," Montana said.

The suits Montana used to make involved a long front and back apron covered with sequins, bead and stones. The covering was heavy and would knock against his legs all day. By the time he would get home, Montana said, the knees of his pants would be worn through and his knees would be scratched.

The apron wasn't the only part of the costume that was heavy.

"When I put that crown on my head it stayed on until I came home" Montana said. "I'd feel like my legs would go down a couple inches."

Walking around looking for other tribes would involve traveling five of six miles, he said.

"Not only walking, but when you meet another tribe, you're dancing," Montana said.

Montana designs a brand new suit every year he masks and has some contempt for those Mardi Gras Indians who don't make their own suits or come up with their own designs.

"People ask me all the time why don't you wear the same suit," Montana said. "I won't do that."

Montana said the first 10 years, he was masking for himself, but that eventually changed and he takes pride in never making the same design twice in his long career. "I know it's a gift, that's why I know I'll never run out (of designs)," Montana said.

Montana's wife, Joyce doesn't mask because she's always been busy doing the slow and painstaking fill-in work of beads and sequins on the intricate suits he wears. "A sequin and a bead at a time," Joyce Montana said. In the weeks preceding Mardi Gras, she said, it wasn't unusual for them to have 15 or more people helping with the suit to get it ready in time.

The couple has gotten some time off from sewing this year, although Joyce Montana said she's been helping her son, also a Big Chief, sew his new suit. However, in a few days, "Tootie" Montana will again begin his yearlong quest to be the "prettiest."

"To stay in it all these years, it is not enough to like it, you have to love it," Montana said.

Contact Us | Homepage